In this post, let’s have a look at how executables are generated, what are the most important executable formats and how they are structured.

How executables are generated?

In this section let’s briefly talk about how the C++ code will be transformed into an executable program.

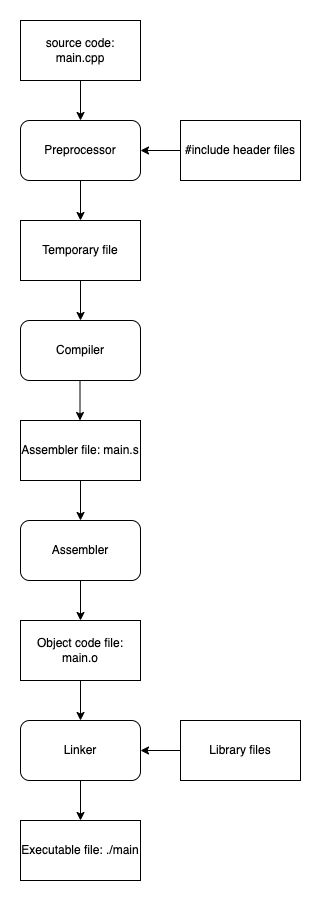

Let’s have a look at the below diagram.

First, the preprocessor will go through your files and will expand all the preprocessor macros. This mostly means textual copies. #include statements will be replaced by the included files, and macros will be replaced according to the macro definitions. But of course, there are also the #if et al. preprocessor directives which might result in actually removing code.

At the end of this step, there is a temporary file that is passed to the compiler. Based on its platform, the compiler generates the corresponding assembly code.

The next step is for the assembler. It takes the assembler code and generates the object code according to the platform. At this point, we almost have an executable, but the references to external code and data must be taken care of. That’s the role of the linker, it will resolve all the links to other headers and libraries. And at the end, you get an executable file.

An overview of the different executable formats

So at the end of the compilation and linking process, we get an executable file. An executable, or binary file might be of different types, of different formats depending on your operating system and compiler settings. Let’s have a look at a few of them.

a.out

You still find in many beginner C or C++ examples the notion of a.out for an executable. They mostly refer to a file name, but in reality, it is also an executable format. It stands for assembler output and it was developed in the 70s. It became a standard format for executables but it’s not widely used anymore, though it’s still supported on some Unix-like platforms.

As it’s simple, let’s have a very brief look at it. It consists of:

- a header describing the size of the file and the location of the different sections and the symbol table.

- the executable code, a.k.a. the text segment

- the data segment

It had to be replaced as it only had limited support for shared libraries as well as for position-independent code. Partly because of these limitations and its structure, it doesn’t support large programs well.

Common Object File Format

A replacement for a.out was COFF (Common Object File Format). While it was originally developed for Unix-like operating systems, some versions of Windows also used it. In its format, it’s similar to other formats, that we are going to discuss. It has a header, a table of contents, text and data segments.

Unlike a.out, COFF supports large programs and debug information, but by today it’s been replaced by other formats, such as ELF, PE and Mach-O.

Executable and Linkable Format

ELF (Executable and Linkable Format) is mostly used on Linux, PE (Portable Executable) on Windows and Mach-O on Apple systems. Their structures are quite similar overall, but the implementation, and how the executable is organized is different. They support a different set of features depending on their target systems, and architectures.

ELF is supported on Linux, Solaris and many other Unix-like systems so it’s a convenient choice for cross-platform projects. ELF supports shared libraries, and position-independent code, so it’s well suited to use in dynamic environments when you have to run multiple instances of a program at the same time. It also supports debug information. ELF is designed both for performance and extensibility. It can be loaded quickly and it runs fast. Its extensible design makes it possible to add new features with relative ease so it can adapt and evolve following the new requirements over time.

Portable Executable format

Portable Executable format was developed for Windows systems. It was designed to be compact so that it’s efficient to store it on disk and transmit over a network. It’s also efficient to load the PE format into memory. Just like ELF it has also an extensible design and supports positivon independent code.

Mach Object

Mach Object or Mach-O in short, is a format used mainly by macOS and iOS. Just like PE, Mach-O is also designed to be compact and to be loaded quickly. In fact, these modern formats are quite similar in features, Mach-O is also easily extensible and it supports positional independent code.

The Mach-O format expanded

As I’m developing on a Mac these days, I decided to have a deeper look at the Mach-O file format. It consists of the following most important parts:

- Header: it describes the file including the number of load commands and the size of each.

- Load commands: they contain information about how to load the file into memory; the locations of code and data and the dependencies on other libraries. We can differentiate among different load commands, depending on whether they describe the entry point of the program or the symbols or locations of shared libraries.

- Segments: one can contain either code or data that are loaded into the memory. A segment always has a name and it can be either read-only, read-write or execute-only.

- Symbols: a symbol is essentially a name that can identify a piece of code or data. These can be either local or global symbols,

- Relocations: they specify how addresses of symbols should be adjusted once the file is loaded into memory. These are the pieces that let a program be loaded at any memory address without conflicting with another program running at the same time.

- Strings: these are typically stored in a separate section of the file and are references by their offsets within the section. They represent names, messages and other text parts within the file.

You might ask what’s the difference between symbols and strings. One key difference between symbols and strings is that symbols are used to represent the names of entities within a program, while strings are used to represent arbitrary sequences of characters. Symbols are typically used to reference specific entities within the program, while strings are simply data that is stored in the file and can be accessed by the program.

Another difference is that symbols are typically used to represent the names of code and data entities within the program, while strings are used to represent arbitrary text that may be displayed or used by the program in some other way.

More on the TEXT segment

Now let’s see what are the different sections in a Mach-O file’s TEXT segment. This is going to be important in order to understand what kind of code ends up where.

The first segment is the so-called __PAGEZERO. Any access to this nulled page results in a crash.

The following segment is the __TEXT. It’s a read-only segment that contains both executable code and constant data. Each program must have at least one of these segments and usually, this is the biggest one.

But just like a molecule is composed of atoms, a segment is composed of sections. Let’s see what are the sections of the __TEXT segment.

The __text section (mind the case!), contains the actual machine code of the program and usually, this section is the biggest of the biggest segment.

The __stub and __stub_helper sections contain the pieces of code that are used for calling and referring to external functions and symbols.

The __const section contains all the constant data used by the program. Let’s remind us again that the __TEXT segment is read-only and also that casting away the constness of a piece of data is undefined behaviour.

The __cstring section contains all the C-style, null-terminated strings. It should contain no duplicates!

The __picsymbol_stub section contains position-independent symbol stubs, allowing the dynamic linker to load the region of code at non-fixed virtual memory addresses.

The DATA segment

Unlike the TEXT segment which contains only read-only data, the DATA segment is a read/write segment. While the read-only text segment can be shared between different processes running the same program, the data segment must be copied by each process as it’s writeable.

Among the most important sections you will find the __data, __const, __bss and __common sections.

The __data section contains all the initialized variables with static storage duration. In the __bss section, you can find also the variables with static storage duration, but only the uninitialized ones. The __common section contains also the uninitialized globals, but only the external ones.

The __const section contains constant data that needs a relocation such as char * const p = "foo";.

Conclusion

Today we had a brief look at the evolution of executable formats, and a deeper look at the Mach-O format that is mostly used on macOS and iOS. Still, what we saw is mostly applicable to other formats too as modern formats are not that much different in their basic attributes. The most important characteristic we saw is that the TEXT segment is read-only and the data segment is read/write. The latter cannot be shared between processes so if you have multiple processes running the same program it’s worth writing code that tries to minimize the usage of the data segment.

Connect deeper

If you liked this article, please

- hit on the like button,

- subscribe to my newsletter

- and let’s connect on Twitter!