Last week I shared with you that despite that I consider myself a careful coder, I managed to break production several times in a row.

It can happen to anyone, though one shouldn’t forget about his responsibility leading to such events.

We can complain about how useless the test systems are, we can blame the reviewers, but at the end of the day, the code was written by one person. In these cases, by me.

Last week, I shared how I slipped and introduced undefined behaviour by not initializing a pointer correctly. Now let’s continue with two other stories, with two other bugs.

A memory leak

Another issue I introduced was once again about pointers. A very knowledgeable C++ engineer told me recently for a good reason that for dynamic memory management you should always use smart pointers, but it’s even better if you can avoid using dynamic allocations at all.

So in one of another monster classes, I found a pointer that was initialized to nullptr in the initializer list, some objects were assigned to it at many different places and at the end, in the destructor, it was not deleted and I couldn’t find where it was cleaned up. A memory leak - unless I missed the cleanup.

The pointer was passed to another object several times, it updated the pointed object and then it was taken back.

Somehow like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

auto aStatus = STATUS::UNDEFINED;

auto aService = MyService{};

aService.setAdapter(m_serviceAdapter);

try {

aStatus = aService.resume();

}

catch (std::exception& e) {

// ...

}

// should now contain the right data!

m_serviceAdapter = static_cast<MyServiceAdapter*>(aService.getAdapter());

All problems can be avoided by using smart pointers.

A very easy option could have been using a shared pointer, but I didn’t want to do it for two reasons:

MyServicelives in another repository and it takes about a day to change, review and deliver a new version (and this is such a lousy reason!)- in most cases where you use a shared pointer, it’s not necessary. It’s simply the easier road to take. I didn’t want to take the easier road.

So I went on using a unique pointer, m_serviceAdapter became a std::unique_ptr<MyServiceAdapter> instead of MyServiceAdapter* and I changed the code like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

auto aStatus = STATUS::UNDEFINED;

auto aService = MyService{};

aService.setAdapter(m_serviceAdapter.release()); // 1

try {

aStatus = aService.resume();

}

catch (std::exception& e) {

// ...

}

// should now contain the right data!

m_serviceAdapter.reset(static_cast<MyServiceAdapter*>(aService.getAdapter())); //2

My reasoning was that at // 1, we don’t want to own the service adapter anymore, we pass the ownership to the service - even if we happen to know that it won’t delete it, it’ll just give back the ownership a few lines later.

At step // 2, we just reset the local adapter from the other service’s adapter. All is fine, right?

At step 1, we released the ownership and at step 2 we got it back.

What can go wrong?

What if MyServiceAdapter assigns another pointer without deleting what it got? It’s a memory leak, but it’s a problem in MyServiceAdapter, not at the call place.

So we could argue that all is fine.

There were about 5-6 functions following the above pattern. But there was another one where there was only the release part, there was no reset.

And with this, I clearly introduced a memory leak and it required a fallback!

So how it is possible that from a small memory leak we went to a bigger one?

That’s something I still don’t understand. I think that with the above change I should have reduced the memory leak because in most cases the pointer got deleted - unlike before. Yet, the stats from production was very clear.

The takeaways for this second issue:

- When it comes to memory management, be extra cautious.

- Don’t go with half solutions. If you assume you pass ownership, go all way through the chain and fix the whole flow.

- Use valgrind more to understand better what happens to your allocated memory.

Know your tools

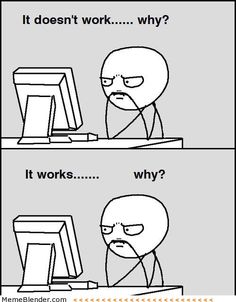

This last one will be shorter, probably a bit less technical. Do you know this meme?

I think this is a great one, and what you can see on the bottom half is actually a quite frequent situation.

Why do I say so?

You have some piece of code that doesn’t work and you have no idea why. Then you fix it.

- Do you even think it through? Do you understand why it works?

- If so, great! But what if not? Do you keep investigating? Or do you simply move on to the next issue?

I’m not here to judge. Often, we don’t have time to continue the investigation and we must take things in the pipe. But it has a serious implication.

Often, what works will not function because it’s the good solution. I wouldn’t even call it a good enough solution. Sometimes it’s just a brittle repair that happens to work under the given circumstances, but it can break any time.

C++ still doesn’t have a build management system that would be the de-facto standard, many companies have their own one, just like us. Therefore I will not go into deep technical details of what happened, but I give you a more high-level view.

Some dependencies were grouped into a package and I made the necessary updates in our descriptors. We were already depending on several packages which were pretty much listed in alphabetical order. By the way, the two most important packages happened to be at the beginning of this sorting.

So I updated the dependencies, put the package in its alphabetical place, then I ran launched the build and the tests. They were all fine.

We loaded into test systems. Nobody raised a word.

Later, we loaded into production. People started to complain.

We broke our stats collector.

We understood quickly that it’s coming from the load so we did a fallback. But what could it be?

I was preparing for an important and high-risk change and I didn’t want to mix it with a routine version update, so I performed this version update separately.

Even that broke our software?

I changed two things:

- I updated the versions of some of our dependencies

- And I changed from where we take those exact same dependencies.

I checked the release notes, the source code of our dependencies. Nothing.

I checked with the maintainers of the package, they had no idea.

I checked the documentation of the build management system and it had nothing on the order of the dependencies.

But as we were out of ideas, we changed the order and lo and behold, that actually worked.

The order of the included dependencies matters when it comes to resolving some non-matching versions.

Many things made this investigation more painful than it should have been:

- the problem was not noticed before the production load, even though it was visible in test already for the users

- it’s not reproducible in local, so there was only a very limited number of chances to try something new each day

- the documentation is clearly incomplete on how versions are inferred

What are the lessons learned?

- Things only work by chance more often than you think

- If you want to grow to the next level, take time to understand your tools

- If you are unsure about your changes, take baby steps and validate them as soon as possible.

Conclusion

Often, things are accidentally working and they can break anytime! You can break them with the best intention, even when you think you introduce some changes that you consider technical improvements. I’d go even further, those are the moments when it’s the easiest to break the system; when you are convinced that you are delivering improvements.

My advice is to take time to understand what exactly are you doing and don’t be afraid of taking baby steps. The smaller the iterations, the easier it will be to understand and debug.

And if shit happens, don’t be discouraged. Keep improving the system!

Connect deeper

If you liked this article, please

- hit on the like button,

- subscribe to my newsletter

- and let’s connect on Twitter!